Dr. Antony Wood is Executive Director of the CTBUH since 2006 and editor of The Tall Buildings Reference Book.

Dr. Antony Wood is Executive Director of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) since 2006, and Studio Associate Professor in the College of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology. Wood and David Parker are editors of The Tall Buildings Reference Book, the significant book on tall buildings published in May 2013. Antony Wood kindly accepted to answer on all our questions.

Which topics does “The Tall Buildings Reference Book” cover? For whom is book intended? What distinguishes this book from other books dealing with tall buildings?

Antony Wood: It covers every topic in tall building, from urban design down to curtain wall design; it’s intended to be a realistic guide for everybody. It is intended for all kinds of professionals in the building industry: architects, engineers, clients, developers, contractors. What distinguishes it from other books dealing with tall buildings? There is no other book like this that’s been published in the last ten, possibly twenty years. All other books are focused on the single subject. All they’re kind of like coffee table books, like reproducing an awards book, or eVolo, or all this other books, but this is the only book that is comprehensively a reference book. It covers all topics. As far as I’m aware.

Which architects made the biggest impact on the development of supertall buildings in the last 20 years?

AW: Depends what you mean by “impact”. If it is in terms of numbers of tall buildings, then I would say that two main skyscraper architects, in terms of quantity, would be SOM and KPF (Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Kohn Pedersen Fox). In terms of quality, I would say Norman Foster, possibly Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), they did some great work. In the last 5 years, the practice that I am really interested in is practice call WOHA in Singapore. I think that they do brilliant work in tall buildings.

PARKROYAL on Pickering hotel, Singapore © WOHA

PARKROYAL on Pickering hotel, Singapore © WOHA

What about Adrian Smith and his work?

AW: The reason I don’t mention Adrian is because Adrian was with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), this I mention, when he did most of his work. Adrian since then has proposed quite a lot of work, but none of the supertall buildings have reached completion yet, since he left Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. So you say which architects but what I given you is which architectural practices. Because any tall building is not the result of a certain person, it’s a whole team.

Can you mention some architecture critics that address theory of tall structures?

AW: I think that most of the criticism, most of the detail analysis and criticism of tall buildings is actually happening within the mainstream newspaper press, not necessarily within journals and architectural publications. Newspapers around the world have a lot to do with the main criticism. People such as Deyan Sudjic who used to be at the Guardian in London comes to mind, Charles Jencks spoke a lot about tall buildings. Quite a few of the critics here in the U.S., Paul Goldberger, Blair Kamin here in Chicago. If you’re looking for critics and by that it doesn’t necessarily mean negative, it could be positive criticism, but analysis, I think, probably more so than any other field, some of the newspaper, architectural correspondence probably written the most revealing insights on tall buildings.

From the last year, CTBUH started to assign an Innovation Award. Most of high-rise buildings, which introduced revolutionary innovations, don’t break the height records. This year 2 buildings get this award. What are the most revolutionary innovations in design and engineering this year?

AW: I think that the two innovations that have won the award this year are absolutely massive. They are major, major innovations. And the first one is the China Broad and method of prefabricated construction. So you, I’m sure, like everybody else, saw on YouTube the thirty-story hotel in China built in fifteen days. That was so jaw-droppingly, amazing. No one has ever done anything like that before. Now they are planning to build the world’s tallest building. Certainly what they have done up to now with this culminating in the thirty-storey building is really important and really impressive. So that’s one of the winners.

The other winner is the Kone ultra rope, and that also is revolutionary because prior to this moment in time, the last two hundred years of elevators have involved pulling a car with a steel rope, vertically. And we’ve now got to the limit of what we can do with a steel rope because it’s so heavy and it’s about five hundred meters. So, Kone is the first company to come up with a viable alternative material to steel rope. And they’ve done this carbon-fiber rope, which is a fraction of the size, fraction of the weight, much, much better in terms of energy performance and therefore not only can enable a thousand meters or beyond even in a single elevator. More importantly, I think it is going to result in better efficiency in energy use in all the tall buildings that employ it. So this year the two innovations are major, major innovations.

T30 Hotel, China. Construction started on December 2, 2011 and was completed in 360 hours

T30 Hotel, China. Construction started on December 2, 2011 and was completed in 360 hours

From 2007, CTBUH awards Best Tall Buildings in 4 continental regions. How dealing and experimentation in high-rise buildings differs in various contexts (American, European, Asian)?

AW: I think it does differ massively. If you look at the entries that we get in each of those categories, they are usually radically different. The American entries are often somewhat boring, if I’m being honest, boring in form, highly commercial, often very well detailed, kind of façade, curtain walls, entrance, lobby, but they are not at all, in my view, pushing the boundaries in the form of the building or, more, importantly, the environmental response of the building.

So if you ask me what are the main differences I would say that the American entries are the most commercial. I would say that the European entries are the most environmental. I think they are the ones that are pushing the possibilities in environmental performance the most. I think the Middle Eastern are the ones where we see the craziest shapes and the craziest forms. The main agenda there seems to be a sculptural form. I mean this is a generalization, not all of them, but I’m saying predominantly. And then Asia is quite interesting because Asia has evidence of all the things I just mentioned. I mean, Asia is just so vast; even China in itself is so vast. There is example of highly commercial, highly environmental and highly gratuitous form within Asia. So it’s more difficult to pin down Asia.

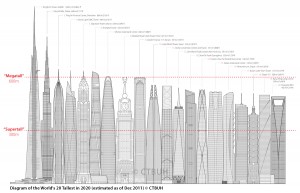

Most of supertall buildings are built in Middle East and China. On CTBUH list of the tallest 20 in 2020, there is only one tower outside Asia. How do you explain that fact?

AW: I think it’s very explainable. The quest for height in tall buildings is predominantly driven by ego and competition. The great height for the title of the world tallest, or the country tallest, is predominantly driven by ego and competition. It’s driven by the need of attention, such us commercial corporative attention, Chrysler Building, Petronas Towers, or now it’s increasingly been driven by urban attention; cities wanting to brand themselves, having the tallest building in the world or the tallest building in the country.

Western cities, a lot of them, don’t feel that they need that attention. So if you look at the tallest 20 in 2020 study, which is the absolute mega-tall buildings by the year 2020, it’s not surprising that there is only one building in America, none in Europe, because: number one, those cities don’t see the need to build the worlds tallest to get attention, and number two, the economics don’t support it. There’s nobody to pay for it. So, it’s not just the case of they don’t need the attention, they don’t have anybody to pay to get that attention, so that’s why there are all in Middle East and Asia.

World’s Tallest 20 in 2020, predicted by CTBUH © CTBUH

World’s Tallest 20 in 2020, predicted by CTBUH © CTBUH

Theoretically, a building could be built Everest-plus-one meter, according to William Baker. Is there a practical limit of building height? At what height do you predict will stop the race for the highest building?

AW: I think the biggest limiting factor on height is financial; it’s not practical, that’s what William Baker means, intend for structural engineering, a kilometer high tower, a mile high tower, two mile high tower, no problem. The structural engineering scenario is the height is related to the size of the base, so technically it couldn’t be achieved. Socially, that is a whole different scenario, what height would people not want to go beyond in a regular capacity. Are you traveling to work every day? Or traveling home every day? That’s what I think we mean by a practical limit. I don’t know what that is. If we set, if we suggested one, every project that came along would challenge it. There’s people six hundred meters high in the Burj Khalifa. They will be even higher in the Kingdom Tower. What high do I predict will stop the race for the highest building? I think for sure we will see a mile high tower; maybe after a mile high people will start to relax a little, but a mile high tower has been a dream of humanity for a hundred years almost and I think we will see a mile high tower probably in the next 20 to 30 years.

Where?

AW: That’s a good question, the obvious answer would be China or Middle East, but I suspect that it may well be in Africa, because we will be getting to a mile high tower by 20 or 30 years’ time, then all these buildings are driven by developing countries and I think that the next region of the world beyond Asia that is gonna be developing will be probably Africa. So the obvious answer would be China or the Middle East but it may well be in Africa or maybe in South America.

Most of new supertall buildings remain empty and unoccupied. Are such structures always profitable? Or normal size buildings could be more profitable? Is high-rise building a status thing in some cases (demonstration of a region’s economic power)?

AW: Well, yeah, it is a status thing. I mean profitability? My answer would be: yes, they are profitable. Otherwise, you would not see the whole world trying to build them. I wouldn’t say that every building is profitable, but I would say that the ones that are the taller ones, the more iconic ones, the ones that speak out more, often end up being the more profitable. For this reason, it depends how you consider profit. If you consider profit as the direct return of money from the building itself, than I would say none of them are profitable. Forget profit, ok? But where they become profitable is in the less tangible return on, for example, if it is corporate building, then the benefits of that building branding the corporation and the impact that have on their operation. People might have bought more of the product, might have bought more Chrysler cars, because Chrysler developed this fantastic building.

And the other thing that’s relevant there is that if you look at the Burj Khalifa or Kingdom Tower or other projects like this, the building, the tallest building is actually, it’s the jewel in the crown. It’s the centerpiece of a huge development. And so, being developed by the same company, by the same developers, so their strategy is to build the supertall building and get huge attention for it and that increases the price of the whole land in the development, not just that tower. So, if you look at Emaar or the Kingdom team development… Did they make money on the Burj Khalifa? I don’t know. Probably not, because it would have cost so much to build. But in terms of, in terms of the return, what that did for twenty other towers and thirty other low-rise buildings on the same area of land and what it did to their stock price or whatever, in terms of their operation, I would say yes, it’s profitable. And if that isn’t the case why do we keep getting all these buildings, all these companies that want to build tall buildings? They are not doing it for altruistic reasons. So they must be profitable, although it is quite a cloudy subject which no one ever, kind seems, able to talk about clearly, at least of all the developers.

Now just can we get back to this supertall buildings remaining empty and unoccupied. I understand where you are coming from with that and I think what you mean is, and I agree with this by the way, a lot of the residential tall buildings are unoccupied, the iconic residential buildings. And the reason for this, and it’s the big problem, is that these iconic residential supertall buildings in London or in Dubai or wherever, they are bought by the super-rich. They are bought as investments. So the product in London or even in Toronto or even in New York, they are bought by people in Israel, Abu Dhabi, Beijing. They are bought by rich people who want to invest in oversees countries. Especially true in the Middle East, because it’s so volatile politically and economically that it is much safer for people with money to invest it in London or Canada or New York. They have no intention of living in these buildings. It’s bought as an investment. But they are kind of rich enough they don’t have to rent them out. So what they do is, they have this mega expensive apartment and they might only stay there two or three weeks out of the year. So that’s why a lot of these building remain unoccupied. They are sold, a lot of them, but they remain unoccupied because it’s not reason in the residential. I think that’s what you are meaning when you say that supertall buildings aren’t occupied.

Kingdom Tower in Jeddah © Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

Kingdom Tower in Jeddah © Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

Is it necessary to build megatall buildings in cases such as Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, when land is not too expensive?

AW: If you look at Petronas Towers, and how much it cost to build those towers, then if you look at profitability, you need to take into account what did that do for the operation of Petronas as a company, and even more importantly what did that do for Kuala Lumpur and Malaysia, what did it do for tourism, what did it do for investment in the country. So when you look at that level, absolutely the building was profitable.

How do you see the development of skyscrapers in the next decades? Will architects need to change their way of thinking about cities?

AW: They need to, because actually I think most skyscrapers are pretty disappointing. I think they’re disappointing as pieces of design. I think they’re especially disappointing environmentally. If you look at almost every country of the world, they have vernacular traditions in architecture that go back hundreds, if not thousands of years and what that created was a world where everywhere was different. And people loved to travel because Belgrade is different, Toronto is different to Beijing, different to Sydney. And what is happening is that tall buildings specifically, modern architecture generally, but tall buildings specifically are just homogenizing the cities around the world. All these cities are coming to look exactly the same and I think that it’s disgusting and it’s something that we need to fight against, and the way to fight against it is to find locally appropriate responses to tall buildings in every location. And locally responsive means that the building relates to its place physically, culturally, philosophically and environmentally; on all those levels. And architects, and more importantly, clients have become lazy, ego-driven and do not see that. They don’t see the need for that and that’s why we have this homogenization of cities and energy consumption. So we need to address that. We need to address it, and in much of my work over the last ten years with my students has been looking how to address that.

I have a set of principles of what tall buildings should become. It involves all manner of things; for example, I don’t think tall buildings should just be a vertical extrusion of a plan. They should vary in form. The air temperature at top of the building is several degrees cooler than at the bottom of the building. So why is the material, the skin and everything else the same? There’s an opportunity there. I think we need to start embracing vegetation into the palette of the building materials. The most important thing, we need to start connecting buildings. You mentioned Petronas Towers, but I often think more about the Pinnacle housing scheme in Singapore or Marina Bay Sands. As we go more vertical in our cities we need to start connect the buildings and create urban habitat in the sky. Because people need that horizontal space for a whole range of reasons, the recreation, the communities, circulation, and it’s ridiculous that we go more and more vertical and not bringing in the horizontal. So will architects need to change their way of thinking about cities? One million percent, yes. I mean in many respects we’re only a few little baby steps along the path we need to tread. That’s the giant path and we’re only a few baby steps along it. We need to consider our cities in a three dimensional holistic way and we’re not doing that. We’re considering them in two dimensional planning way, and then each building becomes the sole responsibility of the developer, and that’s just not good enough.

Marina Bay Sands, Singapore © Safdie Architects

Marina Bay Sands, Singapore © Safdie Architects